Anyone following the P3 trend knows that leaders at colleges and universities are increasingly turning to “public-private partnerships” to achieve campus development goals they can’t afford on their own. As long as those leaders need to do more with less, or in some cases with nothing at all, the trend will persist.

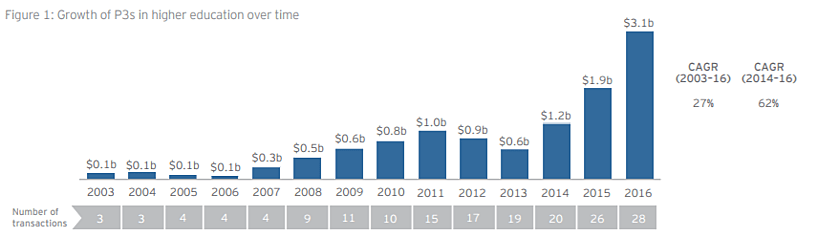

According to Parthenon-EY, only a few P3s were transacted per year in higher education from 2003-2006, with total values around $100 million per year. Between 2014 and 2016 more than 20 projects were transacted per year – totaling more than $6 billion over the three years. In 2016 alone, the total was a whopping $3.1 billion.

Why the shift? P3s have increasingly become more popular with public universities particularly due to reduced public funding. And for private universities, as the cost of operating the campus outpaces the tuition the students and their families can bear, campus leaders there, too, are increasingly considering and using a P3 approach. According to Brailsford and Dunlavey’s State of the P3 Higher Education Industry, 25% of P3s in 2017 were transacted by four-year private institutions.

This trend is expected to continue as demographic shifts and the rising cost of higher education make the competition for students even more intense. This drives the facilities arms race most campuses are participating in – state of the art laboratories and athletic facilities and dining halls and residence halls. Campuses are building and renovating some facilities while being forced to let others deteriorate, increasing the deferred maintenance backlog. P3s can be a desirable option to ease deferred maintenance burdens, keep pace in the facilities arms race, and continue to attract students with the amenities that draw them to campus.

Why go P3?

While an exact definition of a P3 in this context doesn’t really exist, at the highest level, it can be described as a project where a third party develops buildings or infrastructure on behalf of the user. It allows the college to monetize undervalued assets and leverage innovations in the private sector. In addition, a P3 approach provides colleges and universities with more flexibility when building and managing campus projects and often leads to a faster development process. By hiring someone else to develop these projects, they are often “off the books,” allowing campuses to channel their financial and human resources into supporting institutional and educational goals rather than constructing buildings. “Off the books” also shifts control, risk, and often operations to someone else.

One well-known story is the University of California, Merced campus development. UC Merced has the ambitious goal of nearly doubling its student body by 2020 with a $1.3 billion project that would create 1.2 million gross square feet of teaching facilities, research laboratories, student housing, and more. Using a P3, the university selected Plenary Properties Merced, to design, build, partially finance, operate and maintain the campus. The agreement lets the university focus on academics and student success and, because the 39-year term contract covers life cycle costs, it gives the university predictability in budgeting and removes the headache attached with deferred maintenance risk.

In part because of the anticipated success of UC Merced’s large, ambitious P3 campus development project, there is increased interest in the east and other parts of the country to do the same. For example, the University of Massachusetts system recently released two requests for information to potentially pursue similar large, complex developments using a P3 approach for its Amherst and Boston campuses. The Amherst campus RFI is approximately 644,000 to 659,000 GSF and looks to add 1,200 residential beds for students, a 200-room hotel, and an indoor athletic facility. The Boston campus is looking even bigger with 2.5 million GSF and hoping to transform their property near campus into an attractive oceanfront Boston neighborhood with academic, research, retail, residential, and cultural uses, like a Harvard Square. These projects are generating interest at both the local and national level.

While campuses may avoid or reduce a financial expenditure by going P3, they are by no means simplifying their lives — the deals are inherently more complex and require a different approach than a campus-led development. This is something campus leaders need to be ready to manage.

How do you decide if P3 is the right approach for your college or university? What are the risks and the requirements if you decide to pursue a P3? I recently attended a Higher Ed P3 Summit in San Diego. During the conference these questions were debated and owners, advisors, developers, builders, and the design community shared stories about the latest trends, successes, and challenges in P3 project delivery on college and university campuses.

One of my biggest takeaways from the conference was that successful P3 projects result from the right “deal” — program, financial structure, operating model, etc. I also learned that it’s just as important that campus staff have the right mindset to embark on a P3 endeavor. And it’s a very different mindset than a typical campus development project. While there are many advantages to the P3 model, it doesn’t make sense for every institution. When weighing the pros and cons, consider these insights I gleaned from the conference:

What are the risks and who owns them?

I heard many times at the conference: risk should be allocated to those best suited to mitigate it. What does this mean? Colleges and universities are in the business of educating students and fostering research and innovation. Their core business isn’t really feeding and housing people, constructing and operating buildings, or leveraging financial capital most effectively. With a P3, these risks are transferred to the developer. It lets the developer worry about rising construction costs and if the residence hall will fill up, among many other concerns.

But some risks belong with the owner. Developing a contaminated property? Are there seismic risks? Generally speaking, property-related risks that are hard to quantify are best left with the owner, because developers are likely to charge a premium to assume risks over which they have no control.

And what are the risks of NOT going P3? Developers thrive by understanding the market and seizing opportunity. They move fast and get things done. Institutional planning and action is often a long process fraught with delays – and the delays can lead to missed opportunities as well as an increased risk of making a bad decision due to a lack of market understanding. Owners need to be aware of what risks are theirs, what risks have shifted to the developer, and what they can no longer control.

Who is in charge?

A fundamental mind shift is required for campus leaders when embarking on a P3 development. Institutional leaders are no longer in charge. They aren’t constructing a building, they are transacting a real estate deal. Once the real estate deal is done, the developer is in charge of delivering the agreed-upon development.

This can be hard to handle, if not with campus administration, with faculty, staff, and students. When normal campus operations are driven by consensus — and one dissenting vote is considered a tie — it can be a challenge to tell the building user that a developer is in charge. And while a good development partner will work with stakeholders to define the project, they are not able to continually adjust the project based on ever-changing campus wishes.

There is often concern that in addition to giving up control, quality may suffer. It’s critical to select a development partner you trust — one aligned with your goals and the standards you set.

Design standards or performance standards?

Another mind shift is in what the “end product” should be. While traditional delivery methods allow campuses to specify design standards that buildings on campus must adhere to, that doesn’t work in the P3 model. The focus needs to shift from the delivery method to the outcome.

The developer is assuming the market risk with the development and requires the freedom to innovate and deliver a specified level of performance. Laboratories, kitchens, and dorm rooms are often where owners get prescriptive. This can come at the expense of innovation and cost savings. Striking the right balance between prescriptive versus performance is key to success.

Does your team have the right skills and mindset for P3?

A P3 development is different from a construction project and fundamentally more complex. As previously mentioned it is a real estate deal, not a campus-led construction project. As such, the staff overseeing the project on behalf of the institution need to be able to manage the implementation of a contract, not manage a construction project. For example, as I heard at the conference in the case of University of California, Santa Cruz, campus leaders decided an organizational restructuring was required to align skills and functions to manage a P3 development.

A few key aspects when considering the right mind set and skill set include:

- You need a contract management structure

- You need to respond at the pace of a developer

- You can’t change what you ask for — if you do, design changes may lead to performance changes

- You cannot expect change orders — they are prohibited

Can you predict your long-term needs?

Another P3 consideration that requires a mind shift is related to the operations phase. The P3 model means your relationship with the developer will last a lot longer than the traditional design and construction turnover process – typically decades. Therefore, it is paramount to keep the long-term use and vision for the building/s in mind when negotiating the contract. You may be in a contract for a building to operate with a certain use, to a certain performance standard, and for a certain period of time, when a change to the campus mission may require you to renegotiate.

This is a fairly common reason why many college and university leaders avoid the P3 model. If you do decide to pursue a project using a P3 approach, your mindset throughout the duration needs to be that you are in this together. Again, it comes down to selecting a partner you are comfortable with for the long term, and one you have spent significant time with up front to ensure you each understand long-term needs and intended outcomes.

P3 is not for everyone

Although there were many proponents of P3 development at the conference, it’s clearly not for everyone. There are a number of colleges and universities that distinguish themselves from their competition though their careful stewardship of young people. These institutions do consider feeding, housing, and entertaining their students as core to the experience of being on campus and they aren’t willing or able to relinquish the control.

I’ve had campus leaders at two private universities in Boston tell me “it’s not for them,” despite their financial challenges. They don’t want to give up ownership and control of facilities used by their students and faculty. And yet, other institutions, both public and private, across the country are successfully using the P3 model to address some of their needs.

Is P3 in your future?

A P3 approach is fast becoming an attractive option for public and private colleges and universities alike. And not just for small projects but for large, complex developments at colleges and universities across the country. Based on what we’re hearing from our clients, including our experience supporting P3 teams at University of Massachusetts, Boston and Northeastern University, the P3 trend will continue to spike upward.

If you’re competing in the facilities arms race most campuses are participating in, or looking to tackle a large, complex development project for another reason, P3 may be an approach for you to consider. And if you do consider a P3 approach for a campus development project in the future, be prepared for the fundamental mind shift that will be required, as well as an in-depth analysis of your long-term goals, potential risks, and development partners.

Learn more about P3 developments in the blog post, “Momentum for P3 developments on college campuses continues to build.” To talk about P3 trends or how Haley & Aldrich can support your P3 development, contact Liz Fennessy.

Published: 10/31/2017

Author

General Manager, East Business Unit